Day 7: The Land

Song Information

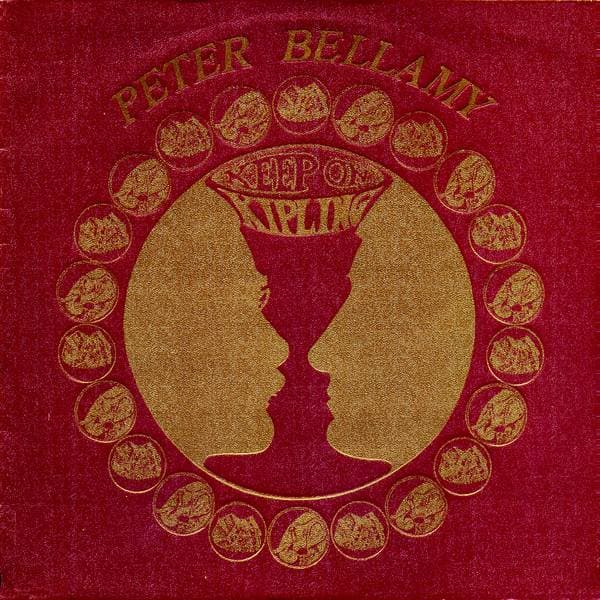

This was recorded on the fourth album of Kipling Poems Keep On Kipling, released in 1982.

An edition of the Kipling Society's Newsletter talks about the fact that Bellamy performed at the Annual Luncheon 1978 and that he took part in several meetings - I do hope he sang it there at least once.

Peter Bellamy set a considerable amount of Rudyard Kipling poems, with at least 6 albums of Kipling material - and is quoted as saying:

Kipling really knew his folk-songs. I contend that the reason other settings of his work have been unconvincing is that the traditional element has been ignored, and thus it has been my aim not only to make good settings, but really to get at what Kipling had in mind when composing the verses

Peter Bellamy, Kipling Journal 188, December 1973

To be honest, I think he could have got away with setting anything and it would have been brilliant.

Some other versions

- Jon Boden did include this in A Folk Song A Day, and I've had the pleasure of hearing him perform it live twice

- Seb Stone also recorded it on his debut album Young Tamlyn's Away

There are some words I didn't understand, so in case you're like me (with thanks to the Kipling Society's reader guide)...

- dreenin’

- Sussex pronunciation of ‘draining’

- jest

- Sussex pronunciation of ‘just’.

- sile

- Sussex pronunciation of ‘soil’

- spile

- Sussex dialect for ‘pile’: protect the bank by driving heavy posts vertically into the bed of the Brook.

- swapped

- Sussex dialect: 'trimmed'. A highly skilled task

Listen to the Song

Lyrics

When Julius Fabricius, Sub-Prefect of the Weald,

In the days of Diocletian owned our Lower River-field,

He called to him Hobdenius—a Briton of the Clay,

Saying: “What about that River-piece for layin’ in to hay?”

And the aged Hobden answered: “I remember as a lad

My father told your father that she wanted dreenin’ bad.

An’ the more that you neeglect her the less you’ll get her clean.

Have it jest as you’ve a mind to, but, if I was you, I’d dreen.”

So they drained it long and crossways in the lavish Roman style.

Still we find among the river-drift their flakes of ancient tile,

And in drouthy middle August, when the bones of meadows show,

We can trace the lines they followed sixteen hundred years ago.

Then Julius Fabricius died as even Prefects do,

And after certain centuries, Imperial Rome died too.

Then did robbers enter Britain from across the Northern main

And our Lower River-field was won by Ogier the Dane.

Well could Ogier work his war-boat—well could Ogier wield his brand—

Much he knew of foaming waters—not so much of farming land.

So he called to him a Hobden of the old unaltered blood.

Saying: “What about that River-piece, she doesn’t look no good?”

And that aged Hobden answered: “Tain’t for me to interfere,

But I’ve known that bit o’ meadow now for five and fifty year.

Have it jest as you’ve a mind to, but I’ve proved it time on time,

If you want to change her nature you have got to give her lime!”

Ogier sent his wains to Lewes, twenty hours’ solemn walk,

And drew back great abundance of the cool, grey, healing chalk.

And old Hobden spread it broadcast, never heeding what was in’t;

Which is why in cleaning ditches, now and then we find a flint.

Ogier died. His sons grew English. Anglo-Saxon was their name,

Until out of blossomed Normandy another pirate came;

For Duke William conquered England and divided with his men,

And our Lower River-field he gave to William of Warenne.

But the Brook (you know her habit) rose one rainy Autumn night

And tore down sodden flitches of the bank to left and right.

So, said William to his Bailiff as they rode their dripping rounds:

“Hob, what about that River-bit—the Brook’s got up no bounds?”

And that aged Hobden answered: “Tain’t my business to advise,

But ye might ha’ known ’twould happen from the way the valley lies.

When ye can’t hold back the water you must try and save the sile.

Hev it jest as you’ve a mind to, but, if I was you, I’d spile!”

So they spiled along the water-course with trunks of willow-trees

And planks of elms behind ’em and immortal oaken knees.

And when the spates of Autumn whirl the gravel-beds away

You can see their faithful fragments iron-hard in iron clay.

Georgii Quinti Anno Sexto, I, who own the River-field,

Am fortified with title-deeds, attested, signed and sealed,

Guaranteeing me, my assigns, my executors and heirs

All sorts of powers and profits which—are neither mine nor theirs.

I have rights of chase and warren, as my dignity requires.

I can fish—but Hobden tickles. I can shoot—but Hobden wires.

I repair, but he reopens, certain gaps which, men allege,

Have been used by every Hobden since a Hobden swapped a hedge.

Shall I dog his morning progress o’er the track-betraying dew?

Demand his dinner-basket into which my pheasant flew?

Confiscate his evening faggot into which my conies ran,

And summons him to judgment? I would sooner summons Pan.

For his dead are in the churchyard—thirty generations laid.

Their names were old in history when Domesday Book was made.

And the passion and the piety and prowess of his line

Have seeded, rooted, fruited in some land the Law calls mine.

Not for any beast that burrows, not for any bird that flies,

Would I lose his large sound council, miss his keen amending eyes.

He is bailiff, woodman, wheelwright, field-surveyor, engineer,

And if flagrantly a poacher—’tain’t for me to interfere.

“Hob, what about that River-bit?” I turn to him again

With Fabricius and Ogier and William of Warenne.

“Hev it jest as you’ve a mind to, but“—and here he takes command.

For whoever pays the taxes old Mus’ Hobden owns the land.